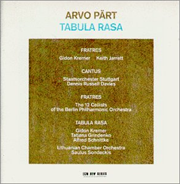

This is the title of an album of music by Arvo Pärt, and of a composition on that album. I have a lot of music by Pärt, but if I had to recommend one record, or one piece, both would be Tabula Rasa. It’s complex, deep, and austere; and contains some of the most beautiful sounds ever recorded. (“5✭♫” series introduction here; with an explanation of why the title may look broken.)

The Context · I’ve written before about Pärt, about how I nearly died listening to Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten, which appears on this record and which I thought was maybe the most beautiful piece of music written in the twentieth century until I bought the record and listened to the title track.

Go to Wikipedia or anywhere else and read about Pärt; it’s a compelling story: Estonian survivor of Soviet orthodoxy, Orthodox devotee, jokes about a “faith minimalism” section in record stores. Quote, from the excellent liner notes:

“In the Soviet Union once, I spoke with a monk and asked him how, as a composer, one can improve oneself. He answered me by saying that he knew of no solution. I told him that I also wrote prayers, and set prayers and the texts of psalms to music, and that perhaps this would be of help to me as a composer. To this he said, ‘No, you are wrong. All the prayers have already been written. You don’t need to write any more. Everything has been prepared. Now you have to prepare yourself.’ I believe there’s a truth in that. We must count on the fact that our music will come to an end one day. Perhaps there will come a moment, even for the greatest artist, when he will no longer want to or have to make art. And perhaps at that very moment we will value his creation even more — because in this instant he will have transcended his work.”

And in respect of the liner notes, I have to mention a company, ECM Records, and its founder/producer Manfred Eicher, the producer not only for Pärt, but for Pat Metheny and also Keith Jarrett’s astounding Köln Concert. I’ll pretty well buy anything with his name on it.

(I have a personal relationship with Pärt; when I was playing cello seriously, I invested some time in Spiegel im Spiegel (“Mirror in a mirror”), endless high slow eight-beat cello notes against surprising piano arpeggiations; if I ever go back to the cello, this is the first piece I’ll play till I get it right.)

The Music · Tabula Rasa has either three or four tracks on it, depending how you count. That’s because one track, Fratres, appears twice, performed once by Gidon Kremer and Keith Jarrett, and once by the 12 Cellists of the Berlin Philharmonic. I apologize for all the name-dropping; that’s what the liner notes say. Fratres is a lovely piece of music and if you play it in company, people will be impressed at your discernment; but compared to the rest of the record, it’s filler.

You see, here’s Arvo Pärt’s dirty little secret: he talks the Orthodox-ascetic talk and his music is spacious and spiritual and serene, but it’s also sensual and dynamic and dramatic, and on both the Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten and Tabula Rasa, he gets right out of control, and this is a good thing.

The Cantus is Pärt’s Big Hit, the one piece you might have heard on late-night radio and thought “Gosh, that’s pretty”. It’s more than pretty; take it home and play it Really Loud and be astounded at the string textures and the fading bell and the descending line and the sense that God just might be listening along with you.

Before we get to the title track, I have to do a little fanboy raving about Gidon Kremer, my personal favorite living violinist (he owns the J.S. Bach solo repertoire). Kremer doesn’t have the most beautiful tone or anything close to it, he just plays all the notes with frightening pitch accuracy for exactly the right length of time at exactly the right volume and isn’t afraid to make the fiddle snarl or scream when that’s what’s called for, and he knows when it’s called for. Eicher captures Kremer at his best on this disc.

· · ·

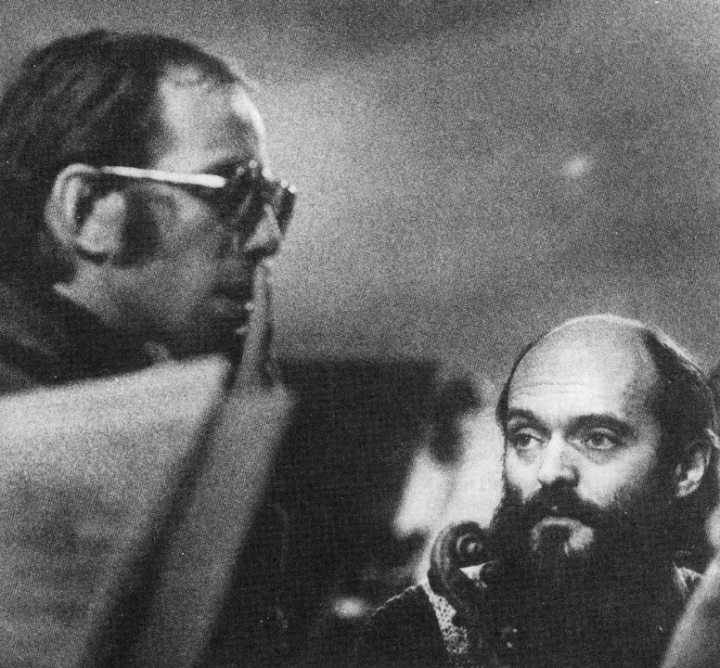

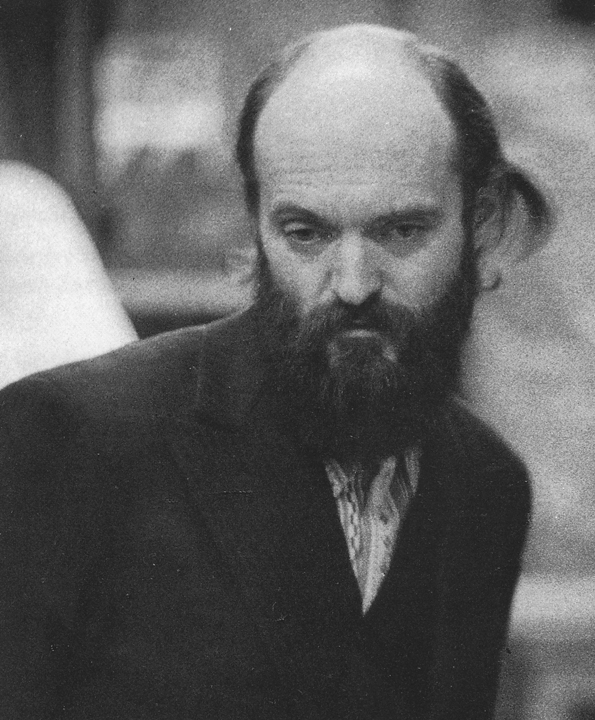

Above, Pärt. Below, Pärt and Kremer. Pictures of the composer are hard to come by, online, so I scanned these from the ECM CD booklet, rather liking the scanning artifacts. This may violate a copyright, but I am probably prepared to argue Fair Use, particularly since I’m plugging their product.

On the 26'26" of Tabula Rasa, Kremer is joined by violinist Tatjana Gridenko, who frequently performs with him; and by Alfred Schnittke (!) on prepared piano, backed by the Lithuanian Chamber Orchestra under Saulus Sondeckis. They all play like gods.

The music is I think a miniature symphony in three movements. The first juxtaposes jagged violin aggro, unbearably-tense silence, elegant string counterpoint, and occasional drily distorted piano commentary. It builds and retreats and builds and retreats and mounts to a climax, unsubtly, unspiritually, unascetically, beautifully. Then that climax doesn’t end, it goes on for three minutes of attacking string ostinatos and prepared-piano snarls; and finally resolves.

Then there’s more. Another sixteen minutes of that justly famous Arvo Pärt Descending Line. A certain amount of musical trickery is going on here: the effect is that the music drifts down an unending scale for minute after minute after minute; Pärt doesn’t let you hear the instruments dropping out and sneaking up a couple of octaves back into the endless descent. And I’ve never heard a musical effect quite like Schnittke’s prepared-piano flourish at the end of each long musical breath; the effect is vaguely Japanese although the tonality is comforting, some long-lost major mode.

It’s possible that I’m going over the top here. But if music moves you, and you retreat into a darkened room, and turn off the background noise, and listen to Tabula Rasa really loud, you might find yourself doing the same.

Sampling It · Don’t be silly, just buy the silver disk, either direct off the Web from ECM or at any other respectable storefront or webfront. Every second on this disk is worth listening to, and the sound quality is beyond superb, and the notions of compressing this music, or encumbering it with DRM, or stealing it from a pirate site, all of those partake of sacrilege.

Pärt’s written lots more music and almost all of it is worth buying. But don’t take my word for it, listen to Tabula Rasa.